RAM/Flash Usage in Embedded C Programs

+-------------------------------+

| |

| |

| |

+-------------------------------+ <----+ Flash Image End

| |

| Copy of Data |

| Section |

| |

+-------------------------------+ ^

| | |

| Read-Only | |

| Data | |

| | | Address

+-------------------------------+ | Values

| | |

| Text | |

| Executable Code | |

| including | |

| Literal Values | |

| | +

| |

+-------------------------------+ <----+ Flash Image Start

In embedded designs, memory, especially RAM, is a precious resource. Understanding how C allocates variables in memory is crucial to getting the best use of memory in embedded systems.

Read More. Understanding memory usage in embedded C++

Memory in a C program includes code and data. Code is by nature read-only and executable. Data memory is

- non-executable

- read-only or read-write

- statically or dynamically allocated

- on the stack or the heap

In desktop programs, the entire memory map is managed through virtual memory using a hardware construct, called a Memory Management Unit (MMU), to map the program’s memory to physical RAM. In RAM-constrained embedded systems lacking an MMU, the memory map is divided into a section for flash memory (code and read-only data) and a section for RAM (read-write data).

Note. This article talks about specifics of the C language implementation using GCC with the ARM Cortex-M architecture. Other implementations differ on specifics, but the basic concepts are the same.

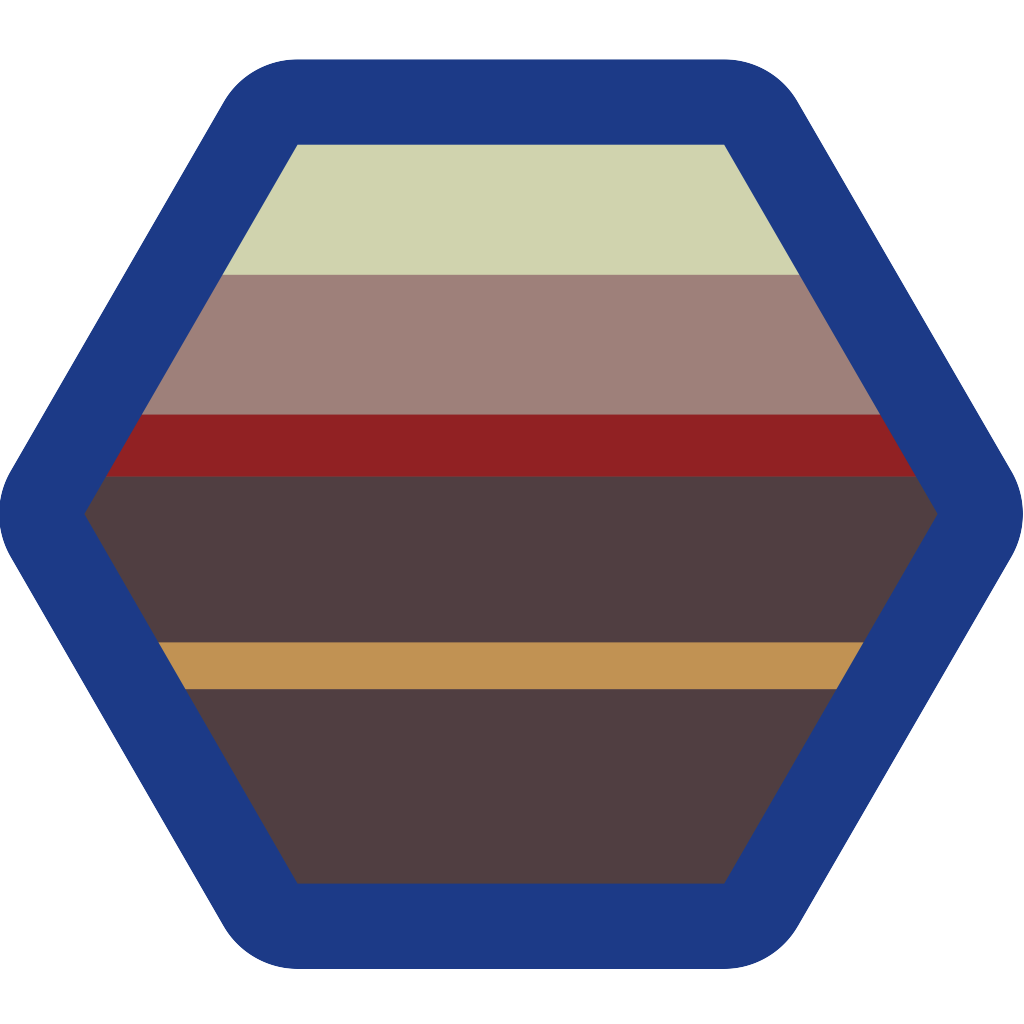

Flash: Code and Read-Only Memory

Code and read-only data are stored in flash memory. The layout of a C program’s flash memory is shown in the diagram above. The beginning of the program (the lowest memory location at the bottom of the diagram) is the text section which includes executable code. This section also includes numerical values that are not assigned to any specific C variable called “literal values”. The read-only data section follows the text section and is exclusively stored in flash memory (note this is only true for some embedded architectures, not all). There is then a copy of the “data” section which contains the initial values of statically allocated variables. This section is copied to RAM when the program starts up.

#include <stdio.h>

const int read_only_variable = 2000;

int data_variable = 500;

void my_function(void){

int x;

x = 200;

printf("X is %d\n", x);

}

In the above code, read_only_variable is stored in the read-only data section as denoted by the const keyword. The compiler assigns read_only_variable a specific address location (in flash) and writes the value of 2000 to that memory location. When the variable x within my_function() is assigned the literal value 200, it references the value stored in a “literal pool” within the text section–at least this is true for the ARM Cortex M architecture. Finally, a copy of the initial value, 500, assigned to data_variable is stored in flash memory and copied to RAM when the program starts. When the program references data_variable, it will refer to its location in RAM.

RAM: Read-Write Data

The following diagram shows the map of the RAM in a C program.

+--------------------------+ <-------+ Top of Stack

| |

| Stack |

| |

| |

+--------------------------+

| + | ^

| | local | |

| | function | |

| | variables | |

| v | |

| | | Increasing

| | | Memory

| | | Addresses

| | |

| ^ | |

| | | |

| | malloc() | |

| | | | Dyncamically

| + | | Allocated

+--------------------------+ + ------------------------

| | Statically

| Heap | Allocated

| BSS and Data |

| |

| |

+--------------------------+ <--------+ Base RAM Address

The read-write data that is stored in RAM is further categorized as statically or dynamically allocated.

Statically Allocated

Data vs bss

Statically allocated memory means that the compiler determines the memory address of the variable at compile time. Static data is divided into two sections: data and bss (there is a wikipedia page dedicated to why it is called bss). The difference is that data is assigned an initial, non-zero value when the program starts while variables in the bss section are initialized to zero. For clarification, see the below example:

#include <stdio.h>

//these variables are globally allocated

int data_var = 500;

int bss_var0;

int bss_var1 = 0;

void my_function(void){

int uninitialized_var;

printf("data_var:%d, bss_var0:%d\n", data_var, bss_var0);

}

When the C program starts, the C runtime (CRT) start function loads the memory location assigned to data_var with 500. This is typically accomplished by copying the value from flash to RAM; this implies that each byte of data will occupy one byte of flash and one byte of RAM. The CRT (C runtime) start function then sets the memory locations for bss_var0 and bss_var1 to zero which does not require any space in flash memory.

The C static Keyword

Static memory should not be confused with the C keyword static. While all C static variables are allocated as static memory, not all statically allocated memory is declared with static. Consider the code snippet:

#include <stdio.h>

int global_var; //statically allocated as a global variable

static int static_var; //statically allocated but only accessible within the file

void my_function(void){

static int my_static = 0; //statically allocated, accessible within my_function

int my_stack = 0; //allocated on the stack

printf("my_static:%d, my_stack:%d\n", my_static, my_stack);

my_stack++;

my_static++;

}

In the above code, global_var can be accessed by any file during the compilation process; static_var can only be accessed with functions that are in the same C file as the static_var declaration. The my_static variable, declared as static within a function, retains its value between successive calls to my_function() while my_stack does not. The output of 5 successive calls to my_function() is:

my_static:0, my_stack:0

my_static:1, my_stack:0

my_static:2, my_stack:0

my_static:3, my_stack:0

my_static:4, my_stack:0

Dynamically Allocated

While the compiler determines the memory address of static memory at compile-time, the locations of dynamically allocated variables are determined while the program is running. The two dynamic memory constructs in C are:

- the heap

- the stack

The stack grows down (from higher memory addresses to lower ones) and the heap grows up. If memory usage is ignored in the design, the stack and heap can collide causing one or both to become corrupted and result in a situation that can be difficult to debug.

The heap is managed by the programmer while the compiler takes care of the stack.

The Heap

The beginning of the heap is just above the last bss variables (see diagram above preceding subsection). The C standard library contains two function families for managing the heap: malloc() and free(). The following code snippet illustrates their usages.

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void my_func(void){

char * buffer;

buffer = malloc(512); //allocate 512 bytes for buffer on the heap

if ( buffer == NULL ){

perror("Failed to allocate memory");

return;

}

//now buffer can be treated as if it were declared char buffer[512]

memset(buffer, 0, 512); //zero out the buffer

sprintf(buffer, "Buffer is at location 0x%lX\n", buffer); //show buffers address

free(buffer); //This frees 512 bytes to be used by another call to malloc()

}

Memory Fragmentation

Dynamically allocated memory is a convenient tool for application developers but must be used deliberately to minimize the effects of memory fragmentation. The following code shows how malloc() and free() can result in fragmented memory:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void my_fragmenting_function(void){

char * my_buffers[3];

int i;

for(i=0; i < 3; i++){

my_buffers[i] = malloc(128); //allocated 128 bytes (3 times)

}

free( buffer[1] );

buffer[1] = malloc(256);

}

The example above allocates 128 bytes three times then frees the middle 128 bytes. Since the freed bytes are essentially sandwiched by the other buffers, malloc() can only use them again when allocating 128 bytes or less. For the final call to allocate 256 bytes, the previously freed 128 bytes cannot be used. Fragmentation problems can be largely avoided by careful use of malloc() and free().

The Stack

Variables that are declared within a function, aka local variables, are either allocated on the stack or simply assigned a register value. Whether a variable is allocated on the stack or simply assigned to a register depends on many factors such as the compiler (including conventions associated with the architecture), the microcontroller architecture, as well as the number of variables already assigned to registers. Consider the following code example:

#include <stdio.h>

int my_function(int a, int b, int c, int d){

int x;

register int y;

char buf[64];

sprintf(buf, "Test String\n");

x = a + b + c + strlen(buf);

y = d*d;

return x*y

}

The paramaters a, b, c, and d to my_function() are stored in registers r0, r1, r2, and r3.

Note. This is true for the ARM Cortex-M but varies between architectures; though most use some number of registers for parameter passing and then pass additional parameters on the stack.

The x variable in my_function() is likely assigned to a register, but if no registers are available, it is assigned a memory location on the stack. The y variable is treated similarly, but because it uses the register keyword, the compiler gives it preference over x when allocating registers. The buf variable is allocated on the stack because:

- it is too large for register allocation

- it is an array

Many architectures have instructions that make working with arrays in memory (rather than registers) perform well. Unlike global and static variables, local variables are only initialized when the program assigns a value to them. For example, before the line x = a + b + c + strlen(buf);, the value of x is whatever the value the register or memory location had before this line was executed. Therefore, local variables should never be used before they are assigned a value within the function.

Registers vs Registers

It is important to make the distinction between the registers used with local variables and those used to configure the microcontroller features and peripherals. Microcontroller datasheets and user manuals refer to “registers” that are used, for example, to turn the UART on and off and configure its baud rate. These configuration “registers” are not the same as the ones mentioned above used with local function variables. Configuration registers are accessed in the same way that RAM is; they are assigned a fixed location in the memory map. Core registers (such as r0) are the memory that is tightly integrated with the central processing logic of the microcontroller and an integral part of the instruction set.

Conclusion

In embedded systems, it is crucial to pay close attention to memory usage. Having a sound understanding of how C allocates variables in RAM and flash both dynamically and statically is key to getting the most out of limited memory.